FEATURE5 October 2016

Behind the label

x Sponsored content on Research Live and in Impact magazine is editorially independent.

Find out more about advertising and sponsorship.

FEATURE5 October 2016

x Sponsored content on Research Live and in Impact magazine is editorially independent.

Find out more about advertising and sponsorship.

Our online behaviour shapes much of the advertising we see, but can it also change how we see ourselves? By Bronwen Morgan

Online advertising in Europe is now worth €36.2bn. According to figures from the Interactive Advertising Bureau (IAB) Europe, it grew by 13.1% in 2015, overtaking the TV market, which is worth €33.3bn.

Within this, behavioural – or interest-based – advertising, which uses web-browsing activity such as pages viewed, searches made and clicked ads to make advertising more relevant to users’ interests and preferences, is big business. Since the end of 2014, there has been a 66% rise in the number of video campaigns being targeted according to behavioural patterns.

Personalisation is, on the face of it, beneficial to both advertisers and consumers; it can make display advertising budgets work harder, as ads are more likely to be served only to the target market. According to IAB UK’s senior programmes manager, Dee Frew, a poll in 2013 showed that 70% of people preferred advertising content to be tailored to their specific circumstances.

But reactions to personalisation aren’t always positive. Many internet users find repeated targeting and personalisation intrusive, while some take offence at the implications behind the ads with which they are targeted. Last year, users of Chinese messaging app WeChat protested against ‘discrimination’ after not being targeted by a BMW ad. According to a story in the Financial Times, many users ‘complained about the humiliation of having their data mined and then ignored’.

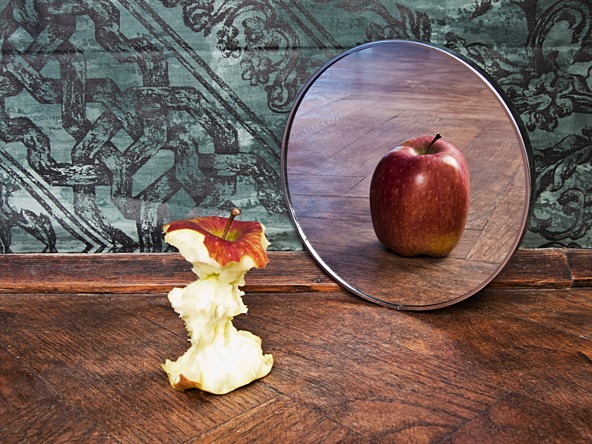

Perhaps even more surprising, however, is the idea that this marketing approach can actually have effects on our behaviour and attitudes of which we are unaware. Recent research by a group of US academics has revealed that behaviourally targeted ads can lead people to make adjustments to their own self-perceptions.

The research, carried out by three professors of marketing, explored the ways consumers respond to ads that use behavioural targeting, compared with how they respond to more traditional forms of targeting.

This was done across a number of studies: the first reinforced previous findings that behaviourally targeted ads act as implied ‘social labels’ – characterisations of people based on their behaviour, beliefs, or personality – and that this results in adjustments to people’s behaviour that are consistent with that label; for example, increased purchase intentions.

The key study demonstrated that when users recognised an ad had been targeted at them based on their previous behaviour, this affected their self-perceptions – and, again, their behaviour. More specifically, consumers seeing a behaviourally targeted ad for an environmentally friendly product subsequently saw themselves as possessing stronger ‘green’ values. This led to a willingness to buy the advertised product and (positively) affected the amount they wanted to donate to an environmental cause. The final study revealed that if an implied label was inconsistent with the consumer’s past behaviour, self-perceptions weren’t adjusted and behaviour wasn’t affected. So if the targeting wasn’t accurate, the implied label wasn’t treated as ‘a valid source of self-information’, and people didn’t adjust their self perceptions to be consistent with it.

Frew believes that the findings from this research are evidence of everyday people becoming increasingly brand-like themselves. “As internet advertising has continued to grow and reach more people, there was always the likelihood that the audience would become aware that they could be spoken to directly by brands, rather than through mass messaging,” he says.

“The era of mass marketing online and buying on CPMs [cost per thousand impressions] is drawing to a close; embracing one-to-one messaging through dynamic creative and real-time bidding will ensure that brands can connect with individuals, as individuals who share their values.

“Social media has highlighted the importance of the individual profile as a micro-brand and this research suggests behavioural advertising could be interpreted as an objective valuation of that micro-brand.

“Further, there could be an aspirational feedback loop as users chase the next strata of social circle – trading loyalty for recognition of core identity properties that they are only subconsciously aware of.”

Clinical psychologist Claire Buky-Webster believes there are a number of potential psychological contributors to these effects. One is that using digital technology is a ‘rewarding’ experience, in that it can be equated to the psychological theory of reinforcement operant conditioning. This describes how behaviour that is reinforced tends to be repeated – and, therefore, strengthened – while behaviour that isn’t reinforced tends to die out. “Quite a lot of the technology is created so that this process happens,” says Buky-Webster. “It’s really important in keeping us coming back for more.”

Also implicated, she adds, is the impact of social groups and social norms. “We’re animals and have evolved in that way – being in groups is how we survive – so it’s really important that we’re included; we want to be part of groups and to be accepted. Advertising must link to that – if it’s clever, it suggests that this [product] is what you need to remain part of the group that you are in.”

Buky-Webster believes that the idea that we have an individual narrative about who we are – known as systemic theory – plays a strong role in driving this behaviour. “We all have scripts that say: ‘I do this; this is who I am. This is my family; this is what we do’,” she says. “They’re determined through our experiences as we grow up, by the experiences of those around us, and by the expectations that people have of us and how we want to be seen. That’s really important in terms of how technology is implicated in that.”

0 Comments